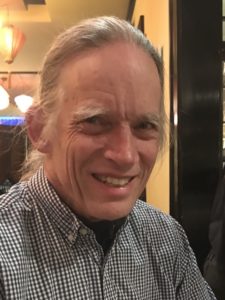

Olympic rower Scott Steketee develops innovative educational software for youths

Their decision was to support the Olympic Project for Human Rights (OPHR). Started by San Jose State sociologist Harry Edwards, the OPHR sought, among other things, to create more opportunity for black athletes and coaches and to bar the then-apartheid South Africa from participating in the Olympics. The Rev. Martin Luther King was an outspoken advisor to the project before he was assassinated in April of that year, sparking days of riots around the country.

The riots, unequal educational opportunities for blacks, poverty, all weighed heavily on the 6-foot-5-inch Steketee and his crew, and six of the nine of them decided to speak out.

“Three weeks after winning the Olympic trials, we were sitting in the Kirkland House Common Room at Harvard holding a press conference with the six of us and Harry Edwards, distributing a press release in support of the ideals of the OPHR. We caught holy hell from the Olympic Committee and from most sports writers around the country,” Steketee said recently over dinner at a West Philadelphia restaurant. Though a half-century has passed, Steketee, a computer scientist, mathematician and principal investigator for a STEM project funded by the National Science Foundation, remains passionate about injustices in America.

Steketee (4th from left) with 1968 Harvard crew. Most endorsed the Olympic Project for Human rights.

The Harvard oarsmen persevered, writing letters to other white Olympians, asking them to listen to what the black athletes were saying about discrimination, poverty and poor schooling in America – to simply understand.

Kareem Abdul-Jabbar, with a certain future as an athlete in front of him, had decided to boycott the Olympics. The Harvard crew, for whom the Olympics was a one-time opportunity, chose to compete and support the black athletes at the Olympics.

A dramatic moment came after two of America’s greatest runners – Tommie Smith and John Carlos – were getting set to receive their gold and bronze awards for the 200-meter dash. The two had planned to put on black gloves and raise their fists while bowing their heads, but one of them forgot his gloves, according to a recent Washington Post story.

Smith (center), Jones (right) and Australian Peter Norman at ’68 Olympics

“The US Olympic Committee was frightened out of their minds that somebody else would protest,” said Steketee. Carlos and Smith, who had broken a world record, were ordered to leave the Olympics. Norman was sanctioned by the Australians (who never allowed him to compete again). And the USOC, after figuring out where Norman’s badge had come from, summoned Hoffman and coach Harry Parker to a hearing on the evening before the final race to determine whether the Harvard coxswain should be pulled from the games, a decision that would make it impossible for the Harvard eight to race.

“We didn’t find out til 11 o’clock on the night before the gold medal race that we would actually be allowed to compete in our finals. It’s a little weird to try to figure out what was going through people’s minds that the crime of loaning a button to an Australian sprinter could provoke that kind of reaction from the USOC,” Steketee said. “They finally did allow us to row.”

Steketee said the crew wasn’t planning a demonstration, given that not all of the members had voiced their endorsement of the OPHR. Besides, he said, “it would not have been appropriate to look like we were trying to upstage the black athletes. So we weren’t considering doing anything. The Olympic Committee thought there was a conspiracy going on.”

The Harvard eight, which earlier in the week had battled equipment problems and lost its stroke oarsman to altitude sickness, finished last in the field of six. “I thought, considering everything, we did reasonably well, finishing seven seconds down on the winning West German crew,” Steketee said.

Still, a month later the president of the Olympic committee, Douglas Roby, wrote a scathing letter to Harvard’s crew coach Harry Parker.

“At one time I, personally, was in favor of disqualifying you and your crew for acts grossly unbecoming to members of our Olympic team.” But, Roby continued, “I am now glad that I did not encourage such a harsh action for I feel the miserable performance of you and your crew at Mexico City will stand as a permanent record against you and the athletes which you led. …Certainly serious intellectual degeneration has taken place in this once great University if you and several members of your crew are examples of the type of men that are within its walls.”

In the end, the ’68 equal rights campaign led by Olympic Project for Human Rights did help push the USOC to ban apartheid South Africa from those games and black coaches and athletes began receiving fairer treatment.

But decades passed without the apology that many thought the USOC owed to Smith and Carlos. In 2016, on the eve of the Rio Olympics, William C. Rhoden of the New York Times wrote a column asking the USOC to publicly apologize to the athletes. It would be, he wrote, “a spectacular gesture of contrition” at a time in American history of tensions over immigration, police use of deadly force, and “inflammatory rhetoric” during a presidential election.

“When I read that column,” said Steketee, “I said, this needs a letter of support from white athletes. So I emailed a bunch of the members of that ’68 rowing team. We only had six of us in the 1968 press conference, but this time 13 of us signed a letter to the Times that was published five days after Rhoden’s column, declaring our support for Rhoden’s call for the USOC to apologize and talking about the fact that here we are 48 years later and we still have the same kinds of inequities.”

This fall, Steketee and his wife went to the 50th reunion of the 1968 Olympics. While Smith never got a formal apology, the USOC asked him to pass a torch at the event and prominently displayed the famous fists photo. (John Carlos was unable to attend).

Steketee (left) greets Tommie Smith at the ’68 Olympics’ 50th reunion

Steketee had hoped the reunion might offer an opportunity for white Olympians to stand up against racism 50 years later, and had emailed some of his teammates about the idea, but he blames himself for not organizing early enough and not being sufficiently clear or compelling in his pitch.

Still, he believes that “white people need to be standing up. The problem we’re talking about here is white racism and white people need to take the initiative on addressing it.”