As we are learning, pandemics can generate some good things: technological advances, for one. And, in Philadelphia’s case, a tourist destination and sport venue that has only flourished over the last two centuries.

But you have to go back to the yellow fever epidemic of 1793. As the disease swept the city, killing 5,000 people that summer (1 in 10 Philadelphians), its leaders believed dirty water was the issue. (A century later it would be shown to be caused by a virus transmitted by mosquitoes.) So, they turned to the pristine Schuylkill River, along whose banks country mansions were being built to improve the city’s water supply.

The system, completed in 1801 and designed by Benjamin Henry Latrobe, burned enormous quantities of wood to power steam engines that pumped water through wooden pipes into the city.

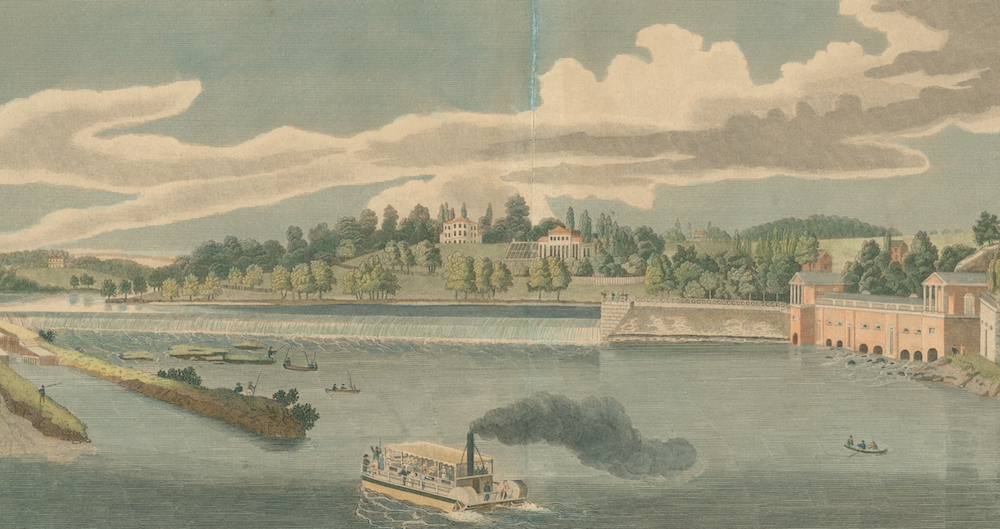

It was a money-losing venture that failed repeatedly. A brilliant civil engineer, Frederick Graff, conceived of a hydraulic system, in which water wheels were used to pump the water up to Faire Mount (the plateau where the Art Museum now sits), and then drain down into the city through cast iron pipes. The project required that a dam be built, to funnel water into the waterwheels.

That was the innovation that changed Philadelphia forever. The 1,600-foot-long dam was the longest in the country, maybe even the world at the time. It was the second most visited place in the United States in the early 19th century, bested only by Niagara Falls. Tourists, standing on an observation platform that extended partially over the dam, were regaled by the waterfall cascading the width of the river and the gracious, neoclassical buildings that housed the pumps. It was said at the time that to visit Philadelphia without seeing Fairmount and its Water Works was like viewing London without seeing Westminster Abbey.

But perhaps more importantly for Philadelphia and the nation, the dam essentially flattened the once-turbulent water behind it, turning the river into what was described as a “lake,” ideal for the hot new sport of rowing. Boat clubs quickly emerged, building shack-like garages for their crew shells along the river. Their charters had pages of rules, like no rowing on Sunday and no women. The Bachelors Barge Club was only for bachelors and its constitution said that if a member married, he lost his voting rights.

By 1858, there were so many clubs — and so many conflicts, including occasional collisions, that the clubs decided they needed an organization to mediate the disputes and to work with the city, which was fast accumulating land along the river for what would become Fairmount Park.

And so was born the Schuylkill Navy, the oldest governing organization for any amateur sport in the United States. And with the development of Fairmount Park came new rules requiring the clubs to rebuild in a more gracious manner, in stone.

Sadly, today another virus has struck the city and the country. The rowing clubs are temporarily closed. Collegiate crews are disbanded for the spring. No boats are on the water. Two of the largest regattas in the world, bringing thousands to Philadelphia each May — the Dad Vail for collegiate rowers and the Stotesbury for high school crews — are cancelled. Also elite rowers, many of whom have trained in Philadelphia, have had their aspirations crushed with the cancellation of the summer Olympics. (See this excellent story by Bob Ford of Philadelphia Inquirer here.)

While on the positive side the Coronavirus 19 brought with it an explosion of indoor innovations we can do while isolated in our homes — from Zoom-like meetings to virtual concerts and museum tours– the outdoors and the thrill of competition beckon.

Once this pandemic has passed, the rowers will be back. Not thanks to this virus, but to the one that coursed through Philadelphia in 1793.