Thomas Eakins, Champion Single Scull (Detail), 1871. The Metropolitan Museum of Art. Image source: Art Resource, NY.

Studying art in Paris in the late 1860s, Thomas Eakins saw rowing not only as healthful but also as mental therapy: when his sister Fanny wrote saying she was discouraged about her piano playing, he suggested that she “take a walk to Fairmount or a row up the river.”

With so much interest in exercise, gyms and sports clubs proliferated in Philadelphia. In 1859, a Philadelphia physician, Paul B. Goddad, opened a predecessor to the soon-to-follow athletic clubs. He called his Establishment, “The Natatorium and Institute for Scientific Instruction in the Improvement of Physical Powers.” Its mission was to apply scientific principles to swimming and exercise “to improve one’s health and physical condition.”

Also springing up were gun clubs, horse clubs, hunting clubs, riding clubs, tennis clubs, and fishing clubs. Cricket was particularly popular among all Philadelphians, and in 1860 there were even three African American cricket clubs “which played the game among themselves.”

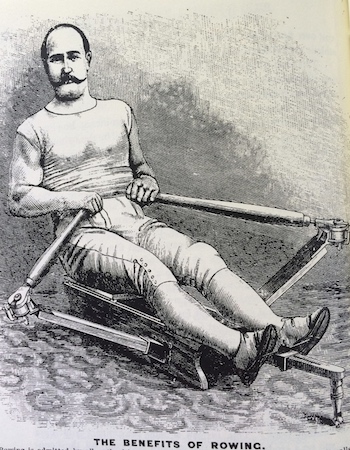

Rowing Machine Ad. Reproduced from Frederick William Janssen, History of American Amateur Athletics (New York: Charles R. Bourne, 1885)

Going well beyond sports, Philadelphians were joining all kinds of fraternal organizations as old social patterns frayed in a city swelling with immigrants from Ireland, Germany, and Great Britain. Rich or poor, artistic or athletic, musical or political, religious or socially concerned, people in the ever more diverse and splintered city wanted to feel as if they belonged somewhere. In droves, they sought the familiarity and camaraderie of a club, where they could make friends, share interests, and in some cases garner prestige. Even those from “the meanest boy’s gang . . . sought a sense of social place and community in club life.” By the 1870s, the city had 24 different singing societies, 91 German secret societies, and 800 private social service organizations, not to mention such rarified groups as the Philadelphia Club and the Union League.

From this culture, boat clubs also emerged. At least two of them sprang from the city’s independent fire companies, which had a history of competition to the point of mayhem. By mid-century, Philadelphia was taking steps to consolidate and modernize firefighting into a citywide force. The neighborhood companies, each one with its own clubhouse, uniforms, social makeup, and status, began seeking other ways to maintain their brotherhood.

Some fire companies turned their energy and fellowship to the river, bringing with them their love of costume and ritual, and a nicknaming tradition. They were not necessarily made up of working-class men. The social status of volunteer firemen typically mirrored the neighborhood they served.

The Bachelors Barge Club, the oldest club in continual existence on the Row, was started by members of the Phoenix Hose Company. It covered the Center City neighborhood around 7th and 8th Streets, among the wealthiest neighborhoods in town at the time. Many of the volunteer firemen were also members of the Yes, Oui, Si Chess Club, which met in the Athenaeum Building.

One of Bachelors’ founders and its president was Israel W. Morris, whose family dated back to the Revolution. Club minutes from the 1850s reveal that Bachelors held its monthly meetings at his family mansion just off Washington Square.