For the Olympics of 1900, the fiercely competitive Vesper Boat Club had recruited the tallest, strongest men they could find, no matter their occupation or social standing. Among them were William Carr, a 24-year-old carpenter born in Donegal, Ireland, who lived with his widowed mother and four siblings; John O. Exley, 33, a teamster whose father had a farm on Hog Island, now part of Philadelphia International Airport; Harry DeBaecke, 21, a machinist; Roscoe Lockwood, a 24-year-old stenographer with two children; and the cox- swain, 16-year-old Louis Abell, of Elizabeth, New Jersey, the son of a carpenter. Also on the boat was James Juvenal, 26, who worked in life insurance and would later become an Olympic coach.

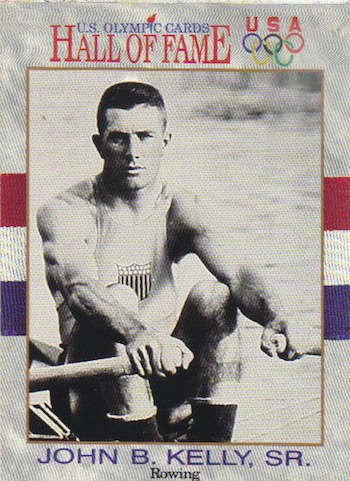

It was into this new era of Boathouse Row that 19-year-old Jack Kelly, with his ideal physique for rowing, at nearly 6 feet 2 inches and 176 pounds, began to make his mark. His hands and arms were strong from his day job in construction, and he was relentless. He would be out on the river at 6:00 a.m., at work from 7:00 a.m. to 5:00 p.m., then back on the river again until dark. On Sundays, he rowed from morning till night.

His star quality was immediately evident. In his first year in junior competition, 1909, he stroked Vesper’s four-oared boat, or “gig,” to victory in the annual Schuylkill Navy Regatta. “Vesper proved a big surprise winning quite easily,” Louis Heiland would write in his 1938 The Schuylkill Navy of Philadelphia. Within three years, Vesper members elected Jack, at age 22, club captain.

Rowing with others in a team boat requires an exquisite level of coordination—all oars dipping into the water in perfect harmony, all bodies pulling back in unison, all arms bringing in the end of the stroke together, everyone coming up the slide with seats rolling at the same speed so as not to check the forward momentum of the boat, all the while as every muscle strains and the lungs scream for oxygen.

John B. Kelly, 23, with hat in hand, with brother’s construction company. Courtesy John B. Kelly III.

Jack preferred sculling in a single, where he could rely only on himself and his own conditioning. In his earliest races, he made classic and humiliating mistakes, sometimes flipping himself out of the boat. He caught “crabs”—placing an oar at a bad angle in the water such that it got sucked under, stalling the boat or even tossing him into the water. Even in those races, Jack would right himself and charge on, astonishingly coming near victory from behind.

He also developed an uncanny way to jump-start the competition by learning to recognize the particular facial motion or gesture made by the judge firing the starter pistol, in the split second before it went off. When a judge at a Boston race, catching on to his technique, warned, “There will be no beating the gun on me” Jack, so the story goes, waited until all the boats had left the mark before turning to him and asking, “Now?” Jack took off—and still won.

Jack Kelly, wearing his “luck of the Irish” green silk cap, was unbeatable. From 1909, when he joined Vesper, until 1920, when he was about to embark for the Diamond Sculls race in England, he had won almost every American sculling title—more than 100 consecutive victories.

World War I had brought a pause to his rowing, though not to his conditioning. He had made a name for himself in the ambulance corps, not so much for aiding the wounded in the trenches of France, but for the pounding he gave French opponents in local boxing matches. He was undefeated in 11 heavyweight bouts, even as he toned muscle and honed to an edge his drive to win.

He was 29 years old in 1920 and had just launched his own construction company, John B. Kelly, Inc.— soon widely known for its logo, “Kelly for Brickwork”—when he turned his focus to that summer’s competition. At the top of his list was the Diamond Challenge Sculls at Henley, where he hoped to trounce the British champion, Jack Beresford. Victory would make Jack the world’s singles champion. The Olympics, being held in Antwerp, Belgium, a site chosen to honor the valiant World War I nation, was almost an after- thought to him.

“I would rather row in the Diamond Sculls than in the Olympics,” Jack told the New York Times that April, as he anxiously awaited British approval of his entry. “It is by no means certain that the English au- thorities will accept me,” he said, citing a possible obstacle: the outrage in England following Vesper’s ungentlemanly behavior at the Henley Royal Regatta 15 years earlier. In 1905, he explained, a Vesper crew had so violated the rules that Henley officials “resolved that they would never permit a Vesper oarsman to row there again. Of course it is foolish that any such reason should bar me but it is possible.”