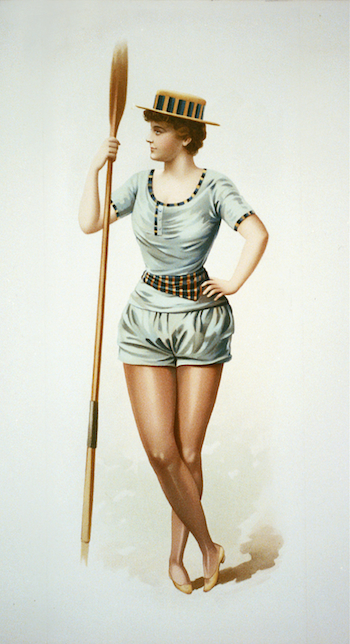

Woman rower, 1889. Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division.

Before Ernestine Bayer got it into her head that she had a perfect right to row; before she arm-twisted her competitive-rower husband in the 1930s to find a way to get on the river; before she and other strong-willed Philadelphia women passed the baton, one to the next, in a decades-long campaign to upend the no-women-here culture of Boathouse Row and American rowing; before all of that, a few—very few—women rowed for sport, and when they did, they were mostly regarded as spectacles. In 1870, Lottie McAlice and Maggie Lew, two Pittsburgh 16-year-olds, raced each other for 13⁄8 miles on the Monongahela River in what was touted as the “first female regatta.” An estimated 8,000 to 12,000 onlookers crowded the shores to watch the oddity, including press from Chicago, Cincinnati, and New York. McAlice, the victor in just under 18 minutes 10 seconds, won a prize of a gold watch.

On New York City’s East River that same year, five teenage girls wearing dresses competed in a three-mile race in heavy 17-foot workboats as spectators lined the banks “for a considerable distance,” with the water “fairly covered” with pleasure boats, barges, and steamships.

In 1888, Newport, Kentucky, oarswoman Mollie King publicly challenged any “female” for a “two mile race for stakes.” It’s unlikely that anyone took her up on it because the many newspapers that announced the contest never published a story on the results.

Courtesy Bachelors Barge Club

Sure, women figured in the muscular, masculine, high-energy culture of crew, but mostly as dates, not athletes. On Boathouse Row, they sat next to their beaux in “ladies boats” for outings upriver or were entertained in the boat clubs’ “ladies lounges.” The notion that women’s rowing would be taken seriously—even becoming an Olympic sport—was so far-fetched as to be laughable.

Epitomizing the opposition to women’s participation in sculling—and other endurance sports, for that matter—was Pierre de Coubertin, the Frenchman who launched the modern Olympics. He was outspoken about his views, famously saying in 1889, “Women have but one task, that of crowning the winner with garlands. . . . It is indecent that the spectators should be exposed to the risk of seeing the body of a woman being smashed before their very eyes. Besides, no matter how toughened a sportswoman may be, her organism is not cut out to sustain certain shocks.”

Even before de Coubertin made his declaration, women’s push into athletics and competitive sports was moving apace. Still barred from walking into the voting booth, women were determined to prove themselves equal to men in every arena. In the last quarter of the 19th century, they conquered the highest U.S. peaks, crossed Niagara Falls on a tightrope (with 38 pounds on each ankle), swam across the Hudson River, defeated men in a walking race, ballooned solo, launched women’s baseball teams (the Blondes vs. the Brunettes), brought tennis to America, and went at one another with boxing gloves.

A few American women even banded together to start rowing groups, though their main interest was health, fitness, and camaraderie, not competition. In 1875, Wellesley College, near Boston, became the first women’s college to offer rowing, but it would be nearly a century before Wellesley women raced another school.