News/Blog

Philly Rowers Storm Europe

Philadelphia’s Schuylkill Navy is sending a small army of athletes to race in Holland and at the World Rowing Cup in Switzerland this summer, including a men’s double, a men’s quad and a lightweight women’s quad.The athletes, who draw from multiple clubs on Boathouse Row, are a taste of what’s to come as the Schuylkill Navy works to establish a “high performance collaborative.”

It’s a fresh and dynamic approach for the clubs, which historically have more often rivaled one another. But with growing competition from other training venues nationally, the clubs of Boathouse Row ware working to make the Schuylkill a premier destination for elite athletes seeking to train for world events.

“While the Europe bound crews consist of 10 athletes, the Schuylkill Navy high performance group includes 40 athletes from the Boathouse Row clubs well as from clubs located on the Schuylkill River above Philadelphia, including the Whitemarsh Boat Club and the Conshohocken Rowing Center,” reports Ed Moran on the website Row2K.

Among the clubs contributing athletes this summer are the Vesper Boat Club, Malta Boat Club and Penn AC.

“For the first time, we are pooling our resources and aiming to have our athletes and coaches from across Boathouse row and upriver row together to showcase the Philadelphia region’s rowing excellence on the international stage,” said Paul Horvat, Commodore of the Schuylkill Navy in its announcement last week.

A Notorious Irish Prison

Reveals the True Kelly Story

Kilmainham Gaol, Dublin

Sure, Kelly had been a bricklayer, and the British amateur rules barred rowers who had worked with their hands. That was one theory that was floated. And, yes, the Vesper Boat Club had also broken amateur rules decades before when its crew accepted money to travel the continent: Henley had barred Vesper from ever coming back.

But the truth lies elsewhere.

Only four years before Kelly’s Henley application, Ireland had plunged into a brutal era of its history, the “1916 Rising.” That Easter, a group of Irish nationalists issued a proclamation of independence, and occupied a number of important buildings in Dublin. The British quickly sent in 20,000 troops who captured their leaders, locked them up in the Kilmainham Gaol, and then summarily executed each one in its courtyard. One of the 15 men, Joseph Plunkett, was granted permisson to marry his fiancée in the prison the day before his execution.

A tragically brief marriage: Joseph Plunkett and Grace Gifford

Another, Joseph Maillin, left behind a toddler son. As he awaited death, he wrote, “I cannot keep the tears back when I think that he will rest in my arms no more.” The martyrdom of these men ignited Ireland’s determination to break free of British rule. The Irish Republican Army was formed and the so-called Anglo-Irish war started.

On March 20, 1920, just as Kelly was gearing up to participate in the most important sculling event in the world – the Champion Diamond Sculls, at Henley – the newly elected mayor of Cork, who was also an officer of the IRA, was shot dead on his 36th birthday in front of his wife and son. The masked assailants proved to be members of the pro-British Irish police. An inquest blamed British Prime Minister Lloyd George.

Just over two months later, Kelly, in Philadelphia, would receive the telegram rejecting his application to row at Henley. “I see no reason for the refusal of my entry,” he said on hearing the news. For decades afterwards, Philadelphia newspapers and Kelly himself – blamed strict British amateur rowing rules as reasons for barring him from the race.

But as the jail and the violent and bitter years following the Easter Rising make clear, there was no way that England was going to allow America’s most famous rower – an Irishman – to trounce a Brit in 1920. A ceasefire was finally declared in 1921 and a free Ireland created, but not until after “Bloody Sunday” of November 1920, when the Irish Republican Army, led by Michael Collins, killed a team of British undercover agents believed responsible for the Cork mayor’s death the previous spring.

By then, Kelly had defeated Jack Beresford in the 1920 summer Olympics – the same English sculler he would have faced had he been allowed to row at Henley.

For the full story of Kelly’s importance to Boathouse Row and the theories around the 1920 Henley games, see my chapter on him in Boathouse Row.

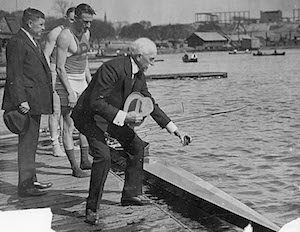

How Edward T. Stotesbury Started World’s Biggest High School Regatta

Stotesbury gives his blessing to a scull Behind him is Garrett Gilmore

Besides that he was civic-mind and had served a president of the Fairmount Park Commission for 26 years.

But little known and largely unheralded was his membership in the Bachelors Barge Club, which he had joined in his 30s, even though he did not row. It was a social thing.

By the 1920s, great rowers were emerging on Boathouse Row who were dominating world rowing (including John B. Kelly Sr. and Paul Costello). Stotesbury’s clubmate, Garrett Gilmore had won the silver single sculls medal in the 1924 Olympics, and like Kelly, he wanted to encourage youth rowing so Philadelphia could maintain its global clout.

So he turned to the wealthy Stotesbury to donate a cup for a single “school boys” race. And so it began. Today the Stotesbury Regatta is the largest high school race in the world, with more than 5000 rowers, both male and female.

The First Women on Boathouse Row? Sedgeley

Sedgeley wraps around the lighthouse

I

n contrast to the very muscular houses of Boathouse Row where, upon entering, one can almost smell the sweat of returning rowers, here, at Sedgeley, the décor is velvet settees and Royal Doulton china tea cups. For this is a women’s social club and one which cherishes its deep history.Sedgeley, at Number 15, is actually where women first got a toehold on Boathouse Row. According to its booklet, “The Light on Turtle Rock, “ Sedgeley was started in 1897 by a group of women who belonged to the downtown all-women’s Acorn Club. They enjoyed canoeing, biking or driving horses in Fairmount Park and wanted a place on the Row so that they could “seek shelter from a thunder storm or have something to eat or drink before returning to town.” Or, to quote Anna Estes Strawbridge (wife of Francis R. Strawbridge of clothing store fame) “a small oasis for friendship, where world burdens can temporarily be laid aside and happiness and pleasure enjoyed.”

I toured the club recently with its president, Deborah Firth, who was disappointed that in my book Boathouse Row, I had not mentioned the dynamic woman who drove the founding of Sedgeley – Margaret Longstreth Corlies. By 1898, within a year of Miss Corlies’ posting of a notice at the downtown women’s Acorn Club, asking for interest in forming a riverside club, Sedgeley had grown to 200 members. Initially, the women rented the old Skating Club building. But wanting their own larger, more elegant quarters, the club in 1902 petitioned Fairmount Park for a location on the Row. The Fairmount Park commissioners turned them down.

Writing about the experience, Miss Corlies (as she was called) later said,: “I was informed by a most prominent citizen that ‘there was no influence or power in the city that could give us the site.’ This nettled me sorely and I determined that the site should be ours.”

“We’re talking 18 years before women had the right to vote!” explained Deborah Firth. “This woman was on the cutting edge of ‘let’s be athletic.’” Miss Corlies would not be denied. She and the other well-connected women, with surnames such as Biddle and Lippincott, brought their influence to bear. By 1903, their new home, designed by architect Arthur H. Brockie, was completed – the first women’s club in Fairmount Park and one of the first women’s boating clubs in the country. (ZLAC, a recreational women’s rowing club, started in San Diego in 1892. The nation’s first women’s competitive rowing club, Philadelphia Girls Rowing Club, was launched in 1938.)

Socializing, too, was important from the start. After excursions in the park, there were refreshments to be had. A pot of tea for one person cost 10 cents; a plate of crackers, five cents. Group luncheons and dinners were often served.

Like the rest of Boathouse Row, Sedgeley has its interesting quirks and preservation challenges. Its enclosed porch, which extends out from the building toward the river, is difficult to heat. And the porch’s new – and historically compatible – windows and frames cost the club more than $12,000. The porch overlooks the spot where a dock once stood.

Its porch is a heating challenge.

The 19th century lighthouse, built before the club now contained within its building, rises up through the living room. It, too, has needed conservation – among the issues to which the club’s foundation is dedicated. Want to take a look inside? Each year, on national Lighthouse Day in August, Sedgeley opens the lighthouse to visitors.

Deborah Firth’s granddaughter climbs the lighthouse

The lighthouse rises through Sedgeley’s living room

But it is the “members room,” with its delicate furnishings that are either original to the house or donated by members, that most captures the heart and charm of Sedgeley. Said Deborah, “We use it lovingly.”

Thank you, SN, for Honoring Me

The umbrella organization of Boathouse Row –the Schuylkill Navy– last week honored my service to the Row by awarding me the 2016 Masters Rower Award of the Year. It’s never before been given for someone who did not excel at rowing. Instead, my honor is for writing. My thanks, especially, to University Barge Club, which nominated me for the award, and for all those who then voted for it. Of course, I could not have written the book without everyone’s help on Boathouse Row. Here’s a video of my little splash in this wonderful pond. [embedyt] http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=dkIqJVt_lIM[/embedyt]At Last: Temple Crew Enjoys New Home

H.F. Gerry Lenfest opens new Temple boathouse

A

fter a battle royal to keep its crew program, Temple University on Thursday officially opened its newly renovated boathouse on the Schuylkill River. On hand was the program’s savior, H.F. Gerry Lenfest, who donated nearly $3 million to assure that Temple crew had a home. Lest we forget, in late 2013, then Temple president Neil D. Theobald announced that he was shutting the vaunted crew program for budget reasons and a howl went up in the rowing world. Lenfest, on the board of Temple, stepped up with the funds needed to repair the East Park Canoe House, the dilapidated longtime home of Temple crew. In writing my book, I interviewed Gerry Lenfest and asked him why he had decided to save Temple rowing. Lenfest, who neither grew up in Philly nor ever rowed replied: “I couldn’t believe that Temple, the city’s principal university, with the most graduates, couldn’t have a place on the Schuylkill. The sport is so germane to the city.” Here’s a link to a video of the new boathouse. Critically, a generous grant from Gerry also saved my book from being a modest black and white production into the full color, heavy stock beauty that it is. Thank you!!A Hidden Philly Gem:The Corinthian Yacht Club

Corinthian Yacht Club, Essington

Atwater Kent Jr., commodore 1942-44

E

ver fly out of Philadelphia International Airport and spot this mansion just south of it, along the Delaware? I had no idea this was a sailing club, and one with nearly as much history as Boathouse Row. For those well-heeled Philadelphians of the 19th century who eschewed rowing, sailing was a suitable alternative, and thus the Corinthian Yacht Club was established in the late 1800s. Among its members were Walter Lippincott whose brother J.B. Lippincott of publishing fame, was a member of the Bachelors Barge Club. Another of the many commodores whose portraits adorn the Corinthian’s walls was Atwater Kent, Jr., son of the Atwater Kent who invented an early ignition system and in the 1920s went on to build (in Philadelphia) the largest radio company in the country. Atwater Jr. ran the Atwater Kent Manufacturing Co. –while enjoying sailing on the side — until his death at age 79 in 1988. Of course, the eponymous museum was funded by the family.

Boyce Budd, 1964 Olympian

The Trials and Triumphs of Seattle’s Early Oarswomen

1905 Rower, U. of Washington

Early UWash women

W

hat a privilege to get a guided tour of the Green Lake Rowing Club and the old boathouse at the University of Washington where Seattle women broke into rowing! Judith Fagerstrom Clark, who was on the Green Lake women’s crew that competed in the First National Women’s Rowing Championship in 1966, took me around her old stomping grounds while I was in Seattle last week. Her memories poured out. For one, she remembers an unexpected slumber party at her house because the Philadelphia Girls’ Rowing Club’s motel reservations had gone amok. Judy’s parents were out of town so she invited some of the Philly gang over, and forever friendships formed. Of course, she became friends with Ernie (Tina) Bayer – daughter of “Mother of U.S. Women’s Rowing” Ernestine and Pennsylvania Barge Club Olympian Ernest. Years later, Judy visited Tina in Philadelphia as well as oarswoman Liz Bergen. A pioneer in her own right, Bergen in 1981 became the first female commodore of the Schuylkill Navy, more than 120 years after its founding in 1858. At that 1966 competition in Seattle, PGRC’s eight-oared crew came in first; second was Lake Washington. Green Lake, with Judy, came in third, though overall Lake Washington scored the most points in that historic regatta.

Judy Clark wtih Vesper mug at Green Lake, Seattle

“Boathouse Row” in Seattle Thursday, Feb. 16

Univ. of Washington Women, 1909

The Women of 1976 Recall Gus Constant

Gus Constant

T

he women who broke so many barriers in the world of crew are still fun and feisty 40 years later. In late January, the Vesper Boat Club honored a number of those selected to row in the very first Olympics with women’s rowing – that would be 1976. Among them were twins Ann and Marie Jonik, alternates in those Montreal Olympics; Pam Behrens and Cathy Menges, who finished sixth in the coxed fours; Sue Morgan and Laura Staines, 7th – place finishers in the coxless pairs; And Diane Braceland, 5th in the coxless double sculls. Joanne Wright Iverson, who launched the National Women’s Rowing Association in 1963 was manager of America’s ’76 crew contingent. In their first appearance at an Olympics, the American women stunned the world. The late Joan Lind won Silver in the single, and the women’s eight-oared boat won Bronze. John Hooten, a Vesper coach in the mid-1970s who helped eight women at the club get to the national camp from which the Olympians would be chosen, acted as MC. He, like the speakers who followed, paid homage to the late Gus Constant, the first person at Vesper to coach women.

The first women Olympians, 1976, with Coach Hooten in 2017.

Tonight you’ve heard stories of long-ago trials,

Of the pioneer Vesper gals rowing long miles –

Achieving great things for the club and girls rowing.

But you must be aware: the momentum’s ongoing.

Vesper women of ‘76 have moved on

<But we and Coach Hooten have been joined by a throng

Of Masters’-aged ladies, all ages and skill

Sculling, racing and rowing til their hearts get their fill.

You at your peak will see time passes too fast

Those few years of glory will always be yours

But countless years lie ahead– you can still have a blast.

Join old friends and new, haul out the old oars.

Pressure to torture yourself as a master? The stakes are not high if you’re not going faster.

If you’re so inclined, there are still plenty of ways

To work hard, race and win like the good old days

Forty years in the sport have provided insight,

And advice we pass on to you young’uns tonight:

Keep pulling along, one way or another

And hold Vesper BC in your heart as a mother.

Jinx Becker: An Early Champion Reminisces

Jinx Becker in 1966

L

ast June marked the 50th anniversary of the Philadelphia Girls’ Rowing Club’s win in the very first National Women’s Rowing Association Championship. Anita (Jinx) Becker Sacco is now wading deep into her memories of that 1966 triumph in Seattle as she organizes a reunion of those pioneering oarswomen some time this year. “I was a member of that crew and sat in seven seat,” she wrote me. “We were having trouble ‘clicking’ when we got to Seattle, and Frank Cunningham, a coach and boatman for one of the clubs in Seattle assisted us greatly. He went out on the water with us and got us focused. He had been a rower at Harvard, I believe, and had a soft spot for rowers of the eastern style. “The following year, 1967, we repeated our first place finish in Oakland, California, and I finished first in the heavy single. Doors started opening for us and 1967, in retrospect, was a charmed year. PGRC produced the first U.S. women’s crew to compete internationally in the European Rowing Championships held in Vichy, France that year.”

The 1966 PGRC champs: From Left: Cox, Marjory Pollack; Bow, Nancy Keeler; 2 seat, Barb DePena; 3 seat, Faye Bardman; 4 seat, Evelyn Bergman; 5 seat, Ernestine Bayer; 6 seat, Carol Shuler; 7 seat, Jinx Becker; Stroke, Nancy Farrell.

that a few years later I would be living in the late Mr. Fleischer’s former home. I admired the work of Thomas Eakins and knew his home had been not too many blocks away. I often wondered how the area actually had looked in its prime. “

As for the reunion, Jinx laments the passing of two members of their crew, Evelyn Berman and Nancy Farrell. “We are all in our 70s, and my philosophy is that we need to do this while we still can.”

that a few years later I would be living in the late Mr. Fleischer’s former home. I admired the work of Thomas Eakins and knew his home had been not too many blocks away. I often wondered how the area actually had looked in its prime. “

As for the reunion, Jinx laments the passing of two members of their crew, Evelyn Berman and Nancy Farrell. “We are all in our 70s, and my philosophy is that we need to do this while we still can.”

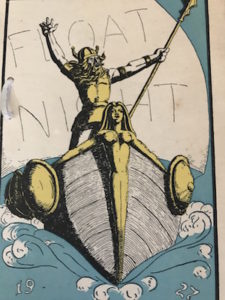

The (1927) Poetry of Wellesley College Crew

Wellesley Rowing Club Pageant 1927

Cleopatra, lift your hand and rouse. The sleeping girl beside your golden bed, That she may sing a silken song Like that, Nile lisps along your barge’s edge.

(I checked for this poem on Google and could find nothing to match it, so perhaps it was written by one of the rowers?)

My thanks to John Schoonover, a history buff with the Wilmington Rowing Club, who shared the small pageant brochure with me. Here are a few photos of pages in it:

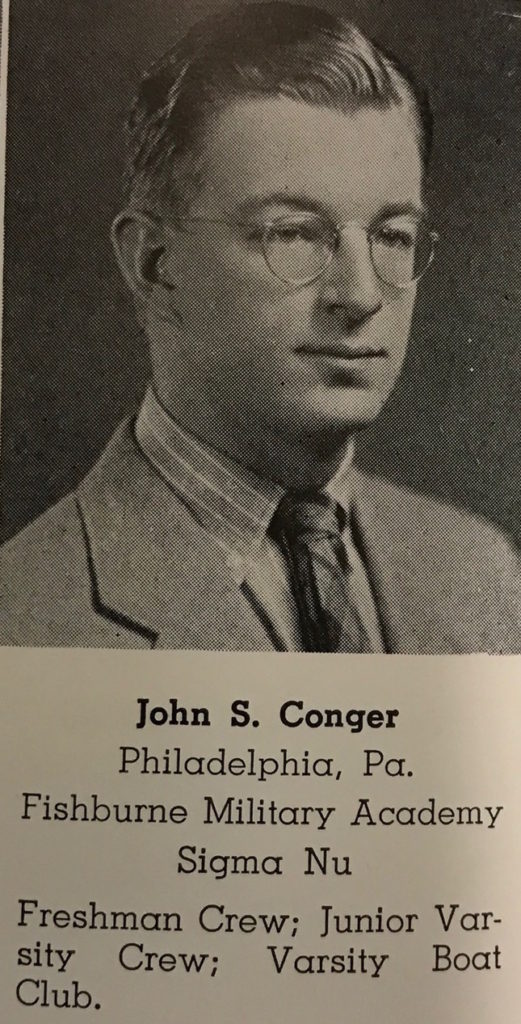

1936 Olympics: What Might Have Been

Would the best-seller Boys in the Boat ever have been written had rising Penn senior John Conger not come down with the mumps? Would the compelling story of a scrappy University of Washington crew making it to the 1936 “Nazi Olympics” never have come to pass? Instead, might the University of Pennsylvania have triumphed in Berlin? After all, the Penn eight did finish a close second to UW at the Olympic trials. For the rest of his life, John (Jack) Conger believed that but for his “childhood disease,” Penn would have won, his son, Dick, told me. “Our father was on the original Penn crew,” slated to compete in the 1936 Olympic trials “until he was quarantined at home with the mumps,” said Dick. “He was heart broken, of course! He told the story many times.”

Bailey, Banks & Biddle made Conger’s medal

Head of the Schuylkill, 2016

Boys’ varsity eight shells wait for their turn at HOSR 2016. Photo by Clem Murray, Philadelphia Inquirer

Anne Boyle Gilmartin

She Rowed in the 1950s

O

n a recent night, when I was talking about my book at the new Narberth Book Shop, Anne Boyle Gilmartin turned up. Now in her 80s, she is as enthusiastic about the Philadelphia Girls Rowing Club (PGRC) as she was as a teenager back in the 1950s.

She reminisced with me about those days, when PGRC –the first competitive rowing club in the country — was still struggling to find women to row against. “I heard about rowing and thought, ‘that sounds interesting,’ Anne told me as we sat in her Drexel Hill, PA home, sparkling with holiday decorations.

What followed was nothing but fun and laughter. She made friends. She flirted. She got great coaching. And she traveled. “We raced on the Potomac, in Boston, in New Rochelle, N.Y.,” she said, showing off her medals.

And she competed in the first major races that PGRC had against a serious women’s team, in 1956 against Florida Southern in Lakeland.

According to research I did for my book, PGRC competed against a sorority team. A Lakeland, Fla. newspaper called the match-up historic — the day “women took over man’s traditional eight-oared shell and launched intersectional competition.”

n a recent night, when I was talking about my book at the new Narberth Book Shop, Anne Boyle Gilmartin turned up. Now in her 80s, she is as enthusiastic about the Philadelphia Girls Rowing Club (PGRC) as she was as a teenager back in the 1950s.

She reminisced with me about those days, when PGRC –the first competitive rowing club in the country — was still struggling to find women to row against. “I heard about rowing and thought, ‘that sounds interesting,’ Anne told me as we sat in her Drexel Hill, PA home, sparkling with holiday decorations.

What followed was nothing but fun and laughter. She made friends. She flirted. She got great coaching. And she traveled. “We raced on the Potomac, in Boston, in New Rochelle, N.Y.,” she said, showing off her medals.

And she competed in the first major races that PGRC had against a serious women’s team, in 1956 against Florida Southern in Lakeland.

According to research I did for my book, PGRC competed against a sorority team. A Lakeland, Fla. newspaper called the match-up historic — the day “women took over man’s traditional eight-oared shell and launched intersectional competition.” Anne rowed that day with Ernestine Bayer, widely called the “mother of women’s rowing,” and a founder of PGRC in 1938. By 1956, the intrepid Ernie was 47 years old “and not to be dissuaded from racing, despite criticism that she was too old,” I wrote in my chapter on women’s crew. PGRC lost, but only by a foot.

Anne remembers being coached by Tom Curran, a champion rower of the 1930s who by the 1950s was also leading La Salle College crew to victory. “He was a rogue,” she said, laughing, as she remembered “the Bear.” But he was tough, too. “If you didn’t dance the way he fiddled, you were in trouble,” she said.

Eying the photo of Curran coaching a men’s eight on page 116 in my book (scroll below), she spied Romeo Boyd and swooned. Sounding like Shakespeare’s Juliet, she recalled calling out to him: “Romeo….Oh, Romeo…”

“He’d take me and throw me in the water. We just had fun.”

Anne rowed that day with Ernestine Bayer, widely called the “mother of women’s rowing,” and a founder of PGRC in 1938. By 1956, the intrepid Ernie was 47 years old “and not to be dissuaded from racing, despite criticism that she was too old,” I wrote in my chapter on women’s crew. PGRC lost, but only by a foot.

Anne remembers being coached by Tom Curran, a champion rower of the 1930s who by the 1950s was also leading La Salle College crew to victory. “He was a rogue,” she said, laughing, as she remembered “the Bear.” But he was tough, too. “If you didn’t dance the way he fiddled, you were in trouble,” she said.

Eying the photo of Curran coaching a men’s eight on page 116 in my book (scroll below), she spied Romeo Boyd and swooned. Sounding like Shakespeare’s Juliet, she recalled calling out to him: “Romeo….Oh, Romeo…”

“He’d take me and throw me in the water. We just had fun.”

We’ve Now Identified All in 1956 Photo

Seated in stroke is Vince Szymkowski as Tom Curran coaches. Got a “Bear” story?

T

hanks to Vince “Murph” Szymkowski (in the boat) and Teresa Dean Fynes (whose father-in-law is in the boat), we may have identified the rowers in this 1956 La Salle crew photo, which appears on page 116 in the book. If some are still incorrect, please let me know! Bow, John Dever, 2 Bill Fynes, 3 Jack Bloxsom, 4 Frank McCloskey, 5 John Maketa, 6 Romeo Boyd, 7 Bob Morro, Stroke Vince Szymkowski, Cox Jack Seitz. If you have stories to share about Tom (the Bear) Curran, please email me at BHRthebook@gmail.comThanks for Hosting Me, USRowing

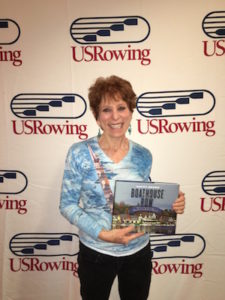

At convention, Springfield, Mass.

M

any thanks to the folks at USRowing for inviting me to their annual convention–Susan, Pam, Sarah and more! My books flew off the table! Loved it when rowers with some history recognized themselves or friends or former coaches in photos.A Huge Turnout At the Union League

Signing at the Union League, Nov 29, 2016

A

truly wonderful event last night, with about 200 people signed up to hear me talk at Philadelphia’s venerable Union League. It was stunning to learn how many people have ties to rowing in this community. Thank you, all!In a 1956 Photo:A Rower Finds Himself

Seated in stroke is Vince Szymkowski as Tom Curran coaches. Who else is in photo?

W

ith much excitement, a rower anxiously awaited his copy of Boathouse Row because friends were calling him to say he was in a photo. Vince Szymkowski emailed me last week: “I got the book yesterday. My picture appears on p. 116 stroking the boat, which I did to two Dad Vail Championships. After graduating from La Salle, I coached with the “Bear” for two years. Later coached at Penn AC. Had 4 National Junior Champions and 1 Bronze medal in the Youth Worlds. I have been known down at Boathouse Row as Vince “murph” Szymkowski.” Thanks, Vince, for letting me know. The photo, from the archives at Temple University’s Special Research Collection, did not identify the men in the boat. Who else can anyone name?Book in the Spotlight:WHYY Radio Times 11 A.M. Wed.

A

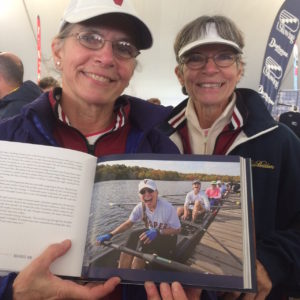

great week for the book: On Wednesday, Nov. 2, I will be on public radio (WHYY) Radio Times, 90.9 at 11 a.m. You can listen to it live here. (The podcast is here.) Main Line Today did a Q&A with me here. Had great fun at the Head of the Schuylkill, where lots of folks I interviewed for the book dropped by.

Emory Clark and Dotty (wearing his 1964 gold medal)

This Weekend on Schuylkill

Rowers to Race

The Jonik sisters at Head of the Schuylkill 2016 show the photo of their 2015 win

E

very year, thousands of people pound down the paved backbone of the city in the sweaty exuberance of the Broad Street Run. This Saturday and Sunday, in another extraordinary test of athleticism and determination open to anyone, the sound will be the beating of oars down a different city artery – the Schuylkill River. Rowing out their hearts and lungs in the Head of the Schuylkill Regatta will be more than 8,500 competitors from 29 states and 12 foreign countries racing in 1,948 boats. They range from high school teenagers and college freshmen just picking up the sport to committed athletes striving for world competition to masters rowers in their 50s, 60s, 70s and yes, even their 80s. About half are now women, a fact that would shock the crowds who witnessed the first big regatta on the Schuylkill on November 12, 1835. That day, seven eight-oared barges, much heavier than today’s hip-hugging vessels, competed. The event “brought to the shores of the Schuylkill more persons than were ever assembled on its banks before,” wrote John Thomas Scharf in his 1884 History of Philadelphia. They “came on horseback and in gigs and wagons and coaches, the number present being several thousand, and the event being also considered by some persons sufficient to justify a cessation of business for the day.” Regattas soared in popularity after 1858, when the emerging boat clubs of Boathouse Row banded together to form the Schuylkill Navy, the country’s oldest amateur athletic governing body. By the 1870s, when Philadelphia artist Thomas Eakins painted his Central High School classmate, champion rower Max Schmitt, as many as 30,000 people would throng the river banks, crowd its bridges and pile onto rowboats and steamers to cheer the racers and wage bets. With baseball and football in their infancies, rowing was then the single most popular spectator sport in the country and Philadelphia was the place to see it. Today, it still is. The races will run Saturday and Sunday from 8 a.m. to 4.30 p.m. For information, go here.Phila. Inquirer Excerpts Book!

What “Old Men” Can Do

O

n Sunday, October 23, 2019, the Philadelphia Inquirer is running an excerpt from my book. It’s already up on line here. There’s also a slideshow and very unrehearsed Q&A with me about the book. I can’t wait to get an actual copy, hopefully in the next couple of weeks.

Temple Coach Gavin White:

On Tom Curran

Tom Curran coaches La Salle College rowers to victory after victory in the 1950s.

T

emple University crew coach Gavin White has been named “Man of the Year” by US Rowing, a huge honor. As a Temple undergrad in the early 1970s, White rowed under the extraordinary and idiosyncratic coach Tom Curran, who arrived at Temple after bringing stardom to La Salle College crew. In an interview for my book about the imprint left by Tom Curran on collegiate rowing in Philadelphia, Coach White, who succeeded Curran in his job in 1978, told me what he was like. On why Curran was called “the Bear”: “He had the biggest hands I ever saw, enormous hands…the biggest paws. He was husky. You could almost see his posture was like a giant bear.” On Curran’s coaching methods: “He was so meticulous. He could take a quick look at the boat and see what you were doing wrong. You might never leave the dock until we finally got it right.” “He taught me everything I know about rowing. He gave the foundation for coaching. He was an amazing character, almost bigger than life.” About Curran’s personality: “He was gruff, especially if you disagreed with him. But he was also funny.” Read about his honor here.My Identity Crisis:

Me as Marketer?

Blasting the news

This week, with the book now headed for the printers, I had an identity crisis, now that I have left the realm of research and writing and am now entering the uncomfortable phase of getting on a megaphone to tell the world about it. When someone said to me, “It’s not you… find another project,” I reached out to other book authors to find out why I might want to be my own call center : My author-friends resoundingly chimed in with lots of reasons I had not been able to articulate: “You love what you’ve discovered writing your book. Now you can share your excitement with others who are fascinated, too.” “It’s what authors have to do. If you don’t push it out, no one will know about it — so what was the point of writing it?” “You’ll meet so many interesting people, and that will lead to things you never imagined.” “You’ll leave every event on a high.” And, as one friend told me several times: “You’ll have so much fun!” What could be better at this stage of life than having so much fun!

Commentary: Women’s rowing first made waves in Philly

AP:Women first joined Olympic rowing at Montreal in 1976.